Democracy in Thousand Oaks: The Meaning of Representation

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”

“Representation means the making present something which is nevertheless not literally present.”

With the sheer array of issues to which government must attend, there is no meaningful way for the people to be involved in every public decision. Even in California, where voters can create and approve laws directly via initiatives, there is still a need for democratically elected representative bodies to perform the public’s work.

Hanna F. Pitkin, American political theorist, author of The Concept of Representation

And in this work, the people can become “present” through their representatives. With this understanding of representation, the award-winning Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, best known for her study The Concept of Representation, discusses a perceived “mandate-independence” controversy [3] about what is expected of the representative.

The argument is best presented by Pitkin’s question: “Should (must) a representative do what his constituents want, and be bound by mandates or instructions from them; or should (must) he be free to act as seems best to him in pursuit of their welfare?” [4] Pitkin argues that in some form “both sides are right… the representative must really act, be independent; yet the represented must be in some sense acting through him.” [5]

Whether one believes that the representative should vote either with a mandate from or independently of their constituents, the authority to represent must be granted by the represented, and this is done through elections.

Simply, to ensure our representatives have the consent of the governed, we hold elections; American self-governance was founded on the concept.

From its beginning as an American state, California included support for education in its original 1849 constitution, requiring the election of a statewide Superintendent of Public Instruction; there were also obligations for districts to keep schools open at least three months every year or lose public funding. [6]

These district schools are governed by local school boards, and the California School Board Association describes the importance of these boards:

“Why do we have school boards? Citizen oversight of local government is the cornerstone of democracy in the United States. It’s the foundation that has lasted through the turbulent centuries since our nation came into being…. It’s appropriate, then, that we entrust the governance of our schools to citizens elected by their communities to oversee both school districts and county offices of education.” [7]

These are fundamental virtues of our American democracy, ensuring that we invest in the education of our people and have democratically elected oversight on how that education is provided. However, the democratic virtues of elected school boards only matter if they are upheld, meaning that we actually hold elections. Otherwise, these very democratic virtues ring hollow.

This chapter focuses on what is meant by representation and whether the actions of local boards to fill vacancies truly honor that concept. However, to judge the actions of local officials with full context, it’s important to know the background, understanding how and why decision makers may use it to justify antidemocratic decisions.

Here, we center on the change in control of the local Thousand Oaks school board and ultimately what is meant of representative government in our democracy.

In 1998, Mary Jo Del Campo was first elected to the Conejo Valley Unified School District Board of Trustees, and in the same year, her husband, Dan Del Campo, won a seat on the Thousand Oaks City Council. [8] Each would serve in leadership positions on two of the city’s most prominent elected bodies – as CVUSD Board President and as Mayor of the City of Thousand Oaks, respectively.

In their re-election bids in 2002, each met different fates. While Mary Jo Del Campo cruised to an easy win for a second term on the CVUSD Board, Dan Del Campo lost his own bid, finishing sixth in the competition for the three four-year Council seats available. [9] Two years later, the former Mayor would seek a position on the Board of Supervisors in neighboring San Luis Obispo County, [10] and Mary Jo Del Campo later resigned her position on the Thousand Oaks school board. [11]

The June resignation allowed for the remaining two years on the term to be filled via special election. With two seats for full four-year terms up for election in November, the special election occurred at the same time as the general election. Los Angeles Fire Department member Mike Dunn won a 43% plurality in a competitive three-way race for the open two-year term; [12] Dunn brought a more conservative voice to the Conejo Valley school board, and he would eventually win re-election for three more terms.

Dunn had served in the minority for most of his tenure on the CVUSD Board, [13] but future elections brought him allies. In 2014, with three seats up for election, two incumbents, including Dunn, won re-election, while John Andersen, a financial advisor endorsed by Dunn, [14][15] bested a field of five other challengers for the open seat. [16] Two years later, a concerted effort by right-leaning groups to win the Board’s majority began.

At that time, conservative activists found more prominent voices in the Conejo Valley – one example included evangelical pastor Rob McCoy, elected to the Thousand Oaks City Council in 2015. [17] In recent years, McCoy has been associated with “far-right” political figures such as Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk and U.S. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia; of McCoy and Greene, reports detailed that “at a Turning Point USA event, another far-right pastor, Rob McCoy, concluded an interview with Greene by saying, ‘Someday, please God, may she be president of the United States.’” [18] McCoy received national attention in April 2020 for flouting early COVID pandemic public health precautions at his church. [19] In response to local community outrage, McCoy resigned from the Thousand Oaks City Council. [20]

Conservative majority of the Conejo Valley Unified School District Board after the 2016 elections

From left to right: John Andersen, Mike Dunn, Sandee Everett

For the two CVUSD board seats in 2016, incumbents Betsy Connolly and Peggy Buckles faced fierce challenges from McCoy-backed candidates Sandee Everett and Angie Simpson. [21] Within Thousand Oaks, city council candidates were limited to receiving just over $500 from a single contributor; however, school board candidates had no such limits. Simpson received a $5,000 contribution from Westlake Village resident Cindy Lane, spouse of a prominent evangelical Christian organizer. [22] David Lane, founder of the American Renewal Project, was profiled the previous year for his nationwide effort to help elect evangelical pastors to office and had supported McCoy in his unsuccessful 2014 bid for State Assembly. [23]

Among over 95,000 votes spread across six school board candidates for the two open seats, Everett topped the 2016 field, receiving nearly 25,000 votes, 7,000 more than any other candidate. [24] The conservative upstarts split the two seats with the incumbent trustees, as Connolly narrowly held on to her seat, edging out Simpson by 175 votes.[25]

With Everett’s win, a right-leaning majority held control of the school board and soon went to work.

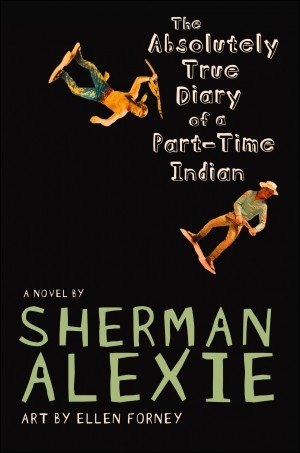

“Part-Time Indian” became the focus on CVUSD Board action in 2017 with concerns over book banning

In early June after taking control, CVUSD Board President Mike Dunn called attention to a book for inclusion in the district’s core literature curriculum; he felt the novel, “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” about a Native American teenager and his decision to attend a nearly all-white public school, was “very controversial” [26] and not age-appropriate for freshman due to language Dunn found objectionable. [27] In years prior, Dunn had voiced opposition in 2012 to “The Kite Runner” on similar grounds as a minority member on the board; however, now conservatives held a majority, and Dunn’s comment sparked community concerns over censorship. [28] Fellow Trustee Betsy Connolly said she was “concerned that a book banning push is on the way.” [29] After a summer recess, the CVUSD Board approved the “Part-Time Indian” 4-1 over Dunn’s objection; [30] however, the vote did not end the literature debate.

In updating the district’s alternative-assignment or “opt-out” policy, one providing options for when a student or their parents take exception to a book on a required reading list, two committees were formed – one made up of CVUSD board members Sandee Everett and Pat Phelps, and the other comprising teachers and administrators; their purpose was to come up with one revised policy to accommodate teachers, students, and parents. [31]

When two members of the teachers committee met with Everett and Phelps to review the final draft policy, Phelps signed off on the language. However, a week later, Everett met separately with two other teachers and presented her own policy, characterized by some teachers involved with the initial draft policy as a “bait and switch.” [32] Under Everett’s proposal, district teachers would be required to alert parents before their children are assigned to read any book identified by the California Department of Education as having mature content, such as depictions of rape, violence, and suicide, and an asterisk warning would be placed on any such title on class syllabi. [33] [34]

Joint letter from The National Council of Teachers of English and the National Coalition Against Censorship in opposition of CVUSD Trustee Everett’s proposal to identify certain books with an asterisk warning

The controversy raised both community and national attention. The CVUSD Board received a joint letter from The National Council of Teachers of English and the National Coalition Against Censorship in opposition to Everett’s proposal, [35] and the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom called the proposal “soft censorship.” [36]

A Thousand Oaks Acorn editorial called out the effort to push forward with “Everett’s hastily written policy,” recognizing that, while not an explicit ban on books, the policy “is indeed a form of censorship, only the slow-burning kind.” [37]

“Just as upsetting as the language of the policy itself is the shameless route the board majority—Everett, Mike Dunn and John Andersen—has taken to foist it on an unwitting public. Precedence and procedure be damned,” the Acorn said. [38]

Standing-room only crowds in opposition to the proposed CVUSD asterisk warning on literature, November 7, 2017. Photo by Maya Chari.

Early November meetings on the prospective policy change drew standing-room-only and overflow crowds, but further troubles came when the policy was finally approved by the Board majority. Last minute changes by Trustee Everett led to copies of her draft policy being made available to the full Board only hours before their meeting, and no copies of the final draft were made available to the public; even the day after the policy was approved, district staff did not have a copy of the policy that reflected the multiple verbal amendments made prior to its approval. [39] Many of those upset with the decision accused the Board majority of violating the state’s open meeting laws, and this wouldn’t be the last time such concerns were raised.

The Board’s new policy relied upon on an approved literature list maintained by state agencies, described by Trustee Everett as having a “California Department of Education warning on certain books.” [40] Trustee Connolly countered Everett and cautioned the Board majority, since according to the California Department of Education (CDE), “it’s not called a warning; it’s an annotation. It’s important that we use the same vocabulary and the same descriptions in our Board policies as the California Department of Education uses,” said Connolly. [41]

Connolly continued: “If they thought that the book was inappropriate, they would not approve it at all,” noting that the explanatory annotations are provided by the submitter of the book for approval, not the CDE. “The annotation is not intended to be a warning; it’s insight from the individual who submitted the book.” [42] When the state agency learned of the new CVUSD policy, the asterisks and the disclaimer languages were removed; CDE staff considered that the CVUSD board was utilizing the “caveats” on book titles in a way they weren’t entirely comfortable with. [43]

Letter from Ventura County Deputy District Attorney Thomas Frye, notifying the CVUSD Board of its violation of the Brown Act, California’s open meeting law

Despite no longer being able to rely upon these state descriptions to identify books displeasing to CVUSD Board conservatives, the Board majority voted in May 2018 to keep the warning policy in place; the local district disclaimer language now referenced the previous CDE disclaimers, even though they were no longer in effect. [44] While the update item was listed on the Board’s agenda for discussion, Trustee Everett circulated amended materials with little notice to the other trustees. When this occurred, Trustee Phelps objected: “I think we’re going to look at stuff that none of us has seen.” [45] Two hours of debate followed, both on the merits of keeping the policy in place and on whether the Board should even be entertaining the topic, given the variety of last-minute amendments that were not known by or available to the public.

The haphazard approach to update to the core literature warning policy led to another brush with skirting California’s Brown Act, the state’s open meeting law. Jenny Fitzgerald, an attorney and candidate in the upcoming 2018 school board elections, contacted the Ventura County District Attorney’s office regarding her concerns. As a result, Ventura County Deputy District Attorney Thomas Frye submitted a letter to the Board regarding Trustee Everett’s prepared materials: “Because the document was created by a trustee and was distributed to the board during a public meeting, the Brown Act required it to be made available for public inspection at the meeting. The failure to make the document available to the public at the meeting was a violation of the Brown Act.” [46] Having to vote again on the issue to remedy the May 2018 vote, the majority left the revised policy in place on a 3-2 revote in August. [47]

CVUSD Resolution #17/18-10, censuring Trustee Dunn, adopted February 8, 2018.

The majority’s policy changes and the manner with which these changes were approved were not the only areas that met with criticism - so was the majority’s handling of that criticism. In early 2018, responding to critiques offered during public comments by an outspoken critic of the Board majority, Dunn emailed the critic’s employer, threatening the company’s owner to link such criticism to his company. [48]

“Thank you for the courtesy of putting your threat in writing,” the business owner replied, viewing the email as an act of intimidation, and subsequently contacted the district attorney’s office and the FBI to what he said was a possible abuse of power by an elected official. [49] Dunn defended his actions, claiming that he was only trying to “protect the district”; [50] community letters soon followed, decrying the trustee’s conduct, stating that “Mr. Dunn is the one who is hurting our school district by threatening to defame a constituent, [and] defame a business that’s been integral in the community for over 30 years.” [51]

At the following meeting, the Board voted 4-0 to approve a resolution authored by Trustee Connolly to censure Dunn, condemning his actions as “a violation of the Board Bylaws as well as unacceptable, unprofessional, irresponsible behavior that cannot be tolerated.” [52] Dunn chose not to attend the meeting at which the censure motion was agendized. [53]

Such was the tenor of the 2018 elections for control of the CVUSD Board.

The two years under conservative control focused electoral attention. With three of the five at-large seats up for election, those held by Trustees Dunn, Andersen, and Phelps, Board control was again at stake.

With multi-candidate at-large elections, voters may vote for as many candidates as there are seats available; in this case, voters can choose up to three candidates, and the top three voter-getters are elected. In these types of elections, slates are sometimes formed, either formally or informally, as a strategy to consolidate votes behind their preferred candidates.

Conservatives formed a group of three candidates for the open seats, including incumbent Mike Dunn. However, Dunn ally and current Board President John Andersen chose not to seek reelection, so the slate was completed by Angie Simpson, who narrowly lost to Betsy Connolly two years prior, and Amy Chen, a self-described “founding director of a new nonprofit,” although opponents challenged whether the organization existed in any form other than on paper. [54]

CVUSD Board Trustee candidates endorsed by Conejo Together in the 2018 election

From left to right: Jenny Fitzgerald, Bill Gorback, Cindy Goldberg

To counter the conservative trio, a broad group of teachers and parents formed Conejo Together to support a slate of new faces for the Board, given current trustee Pat Phelps’ choice to retire after twenty years on the panel.

The candidates supported by Conejo Together included Jenny Fitzgerald, the attorney who highlighted the CVUSD’s May 2018 Brown Act violation, Bill Gorback, a school counselor and previous CVUSD Board candidate, and Cindy Goldberg, a longtime advocate, CVUSD and Chamber of Commerce committee member, and Executive Director of the long-standing Conejo Schools Foundation nonprofit.

Heading into the November 2018 elections, a late item found its way onto an October CVUSD Board meeting: Trustee Sandee Everett targeted fellow Trustee Betsy Connolly with her own motion of censure. [55]

Everett specified four instances that, in her opinion, demonstrated inappropriate social media use, including a post from nearly one year prior, a recent email from Connolly expressing support of the Conejo Together slate of candidates, and another social media post that turned out to be from a parody account, wrongly attributed to Connolly by Everett. [56]

“This is their October surprise, but it’s not a very good one,” said Connolly, noting the timing relative to the upcoming November election. [57]

CVUSD Trustees Connolly and Phelps turned the tables on Trustee Everett’s “October surprise” to censure Connolly before the 2018 election

From left to right: Betsy Connolly, Pat Phelps

Everett supporters spoke on the censure topic during the public comments section at the beginning of the meeting, leaving shortly afterwards rather than wait the three-and-a-half hours to speak on the agenda topic itself. When the proposed censure resolution came up for consideration, around twenty speakers remained to offer their comments, nearly all supportive of Connolly. [58] However, no one made a motion to consider the resolution, even though Everett placed the item on the agenda. Had no motion been made, the resolution would have fallen off the agenda, and no discussion from either the Board members or the public in attendance would occur. [59]

Given the silence from the conservative majority, Connolly asked Phelps to move the resolution for consideration, so that the public could speak to the topic. Everett had previously tried to remove the topic from the agenda; however, Board President Andersen stated that withdrawal would need to have occurred before the agenda was approved. Connolly felt Everett’s attempt to withdraw the resolution was a “clever ploy” to deny her supporters the opportunity to voice their opinions. [60] When the vote occurred, the censure motion failed 1-2; Connolly and Phelps voted the resolution down, and although present, Dunn and Andersen abstained from the vote altogether. [61]

The two years of drama on the Conejo Valley Unified Board ended with an electoral sweep by the Conejo Together candidates. Goldberg, Fitzgerald, and Gorback outpaced the field by more than 2,000 votes, serving as a repudiation to governance by the conversative majority, including a disappointing sixth for Dunn after serving 14 years on the Board. [62] Trustee Betsy Connolly now served in a four-member majority with fellow trustee Sandee Everett serving as a lone conservative voice on the panel. The board soon reversed the controversial literature policy put in place by the previous majority. [63][64]

The next election cycle brought changes in board composition and the nature of how voters would be represented. Shortly after the 2018 election, the CVUSD Board voted to change their elections from at-large contests to elections by district.[65] Earlier in the year, the school district received a demand letter on behalf of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, stating that at-large elections in CVUSD are “racially polarized, resulting in minority vote dilution” in violation of the California Voting Rights Act. [66]

Starting in 2020, Conejo Valley USD Board Trustees were elected by area versus districtwide

In evaluating whether to make the change willingly versus fight the demand, the district looked at the success records of other cities. According to information available at the time, challenging the demand could prove futile and cost millions of dollars in the effort. Several years before, the City of Palmdale spent around $7 million to fight a CVRA claim at trial unsuccessfully, eventually settling for $4.5 million. [67] At the time of CVUSD’s deliberations, the City of Santa Monica had also lost its fight at trial, spending $5 million in its own defense and owed an estimated $10 million to the plaintiff; [68] in the years that followed, after an appeals court victory for the city, the California Supreme Court granted review and asked parties to brief the following issue: What must a plaintiff prove in order to establish vote dilution under the California Voting Rights Act? [69]

CVUSD Board Trustee candidates endorsed by Conejo Together in the 2020 election

From left to right: Karen Sylvester, Lauren Gill

The Board agreed to change their trustee elections shortly after the 2018 elections; [70] the terms for Trustees Connolly and Everett ended in 2020, and these seats were the first to be elected under the new “by district” model. First elected to the Board in 2008, Connolly chose not to run for reelection after serving three terms, [71] and Everett, now seeking election from the Newbury Park district Area 5, sought her second term.

After successfully backing Trustees Goldberg, Gorback, and Fitzgerald in 2018, Conejo Together backed Lauren Gill to run against Everett and Karen Sylvester for the Westlake Village-based Area 1. Both Conejo Together candidates won their contests, Sylvester by a comfortable 5,000 vote margin and Gill by a narrower 500 vote edge over the incumbent Everett. [72] After two election cycles, Thousand Oaks voters swept conservatives completely off the local school board.

The previous two elections seated all five Conejo Valley Unified School District trustees with candidates backed by Conejo Together, and only six months later, more changes would come to the board.

In May 2021, with 18 months remaining on her term, Board President Jenny Fitzgerald announced she would be resigning her position. [73] In a statement on Facebook, Fitzgerald announced that she would be relocating out of the area and would be stepping down as trustee after the end of this school year. [74]

Facebook post by CVUSD Trustee Fitzgerald, announcing that she’d be relocating out of the area and resigning from the Board, May 20, 2021

In her post, Fitzgerald, an attorney by profession, stated her understanding of the Board’s options available: “You are likely wondering what my vacancy will mean for the board. Based on my own research, it is my understanding that the timing of my departure will provide the board the option to either order an election (which comes with a financial cost) or make a provisional appointment using an application process for the remainder of my term (then having an open election for the seat as normally scheduled).” [75]

California’s Education Code governs how vacancies can be filled to local elected school boards; boards can either call for an election or appoint someone for the remainder of the team. [76] However, timing plays a critical role in managing public perception of the most reasonable options available.

While Fitzgerald had announced her intention to resign, no vacancy actually yet existed. Before the Board could take action to fill her vacancy, Fitzgerald needed either to create the vacancy officially by stepping down from the panel or to submit a resignation letter with the county superintendent of schools containing a deferred effective date.[77] If the Board wanted to hold a special election to fill the Area 2 seat, no election could yet be called until Fitzgerald submitted a letter of resignation.

Given Fitzgerald’s announcement in May, an election to fill the one year remaining on the term could be held in November, when most voters expect elections to occur. To accommodate an election on November 2, 2021, the Education Code requires an election be held not less than 130 days after the order of the election, [78] meaning the CVUSD Board would need to call for a special election by June 25, 2021.

However, even with public knowledge of the pending vacancy for a full month, the precise date of Fitzgerald’s official resignation was oddly coincidental. The date on which Fitzgerald’s letter was submitted: June 25, 2021. [79]

The timing of Fitzgerald’s official resignation mattered, since it precluded the Board from considering a November 2021 election; Fitzgerald’s official resignation came too late. Now, any contemplated election would be held in the spring of 2022, coming at a less familiar time and at increased cost (estimated at $135,000) [80] with only six months remaining on the term. The Board moved swiftly, agreeing at the first meeting after Fitzgerald submitted her resignation to forgo an election and to fill the vacancy by appointment. [81] A month later, the Board appointed longtime parent volunteer Rocky Capobianco to fill the vacancy. [82]

State law does, however, offer voters the opportunity to hold an election if the school district board vacancy is filled via appointment. Under the Education Code, if valid petitions from 1.5% of registered voters within the district are submitted to the county superintendent of schools within 30 days of the appointment, the appointment itself is terminated, and a special election would be held. [83] Given the size of CVUSD’s Area 2, this equated to 219 valid petition signatures; [84] even though petitions containing 315 signatures were submitted for an election, only 161 were found to be valid, so the election effort failed and Copabianco’s appointment was upheld. [85]

As we’ve seen in other election-related episodes in Thousand Oaks governance, when given the choice to let voters elect their leaders, decision makers will surprisingly often choose to forgo elections.

Just as with the 2005 and 2012 Thousand Oaks City Council appointments, the perceived costs of elections guided the 2021 CVUSD Board decision to appoint, even though there was full recognition that election costs are relatively miniscule.

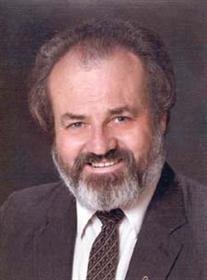

Lee Laxdal, Thousand Oaks City Councilmember (1980-1989) and two-time Mayor (selected 1984, 1987)

Laxdal resigned and moved up his resignation to accommodate a November election to fill his vacancy

CVUSD Board President Bill Gorback told local reporters that, while the cost of a special election may seem small, estimated at $135,000 for an Area 2 election compared to the district’s overall budget of over $200 million, there’s a lot the district could do with that money to serve students. [86]

It can be argued that the CVUSD had only two choices: hold an off-cycle election or appoint someone for the rest of the term. However, with Fitzgerald making her intent to resign public when she did, there was a third choice: urge Fitzgerald to submit her resignation letter sooner, giving the Board enough time to call a November election and a newly elected trustee a full year on the CVUSD board.

When we value democracy and default to electing our leaders, this would have been the course of action; instead, the coincident timing of Fitzgerald’s resignation made an election more costly, less convenient, and easier to rationalize away in favor of appointment.

Such a scenario isn’t even unprecedented in Thousand Oaks. In June 1989, Councilmember Lee Laxdal announced that he would be resigning from the Thousand Oaks City Council effective August 1 to take an engineering position in Australia with his employer. [87] To accommodate timing for a special election in November of 1989 as opposed to the following April, Laxdal moved up his resignation, and the Council voted unanimously and without significant fanfare to call for the special election to fill the vacancy. [88]

Those in control of the Conejo Valley Unified School District Board saw the turmoil and uproar with conservatives in charge of the panel, and this may have drove the current Board toward appointment. Yet, even with the community’s recent electoral backing in the previous two elections, when the Board had a 100% chance to determine the outcome through appointment versus even, say, a 90% chance through an election, appointment was the chosen course. When the likelihood of holding elections is dependent on whether those in power can control the outcome, our democratic institutions are at risk.

We saw from the 2012 Thousand Oaks City Council appointment chapter that, even when the costs of elections were minimized to the greatest degree, decision makers will still choose to forgo elections. Unfortunately, rationalizing actions to keep power is a human trait, not necessarily a partisan one.

In a community such as Thousand Oaks, the overall costs of city council and school board trustee elections are extremely small relative to overall budgets. Regular elections only occur every other year, and the need for special elections to fill vacancies are even less frequent. In Thousand Oaks, after the 1995 special election to fill a city council vacancy, there were six council vacancies over a 25-year period. [89]

On the local school board, the need for special elections has been even more rare. Since the initial special election in 2004, when Mike Dunn was first seated on the CVUSD Board, no vacancies occurred until Fitzgerald withdrew from the Board in 2021. Over that period between vacancies, the Board oversaw budgets exceeding $3.5 billion, [90] yet no costs were spent on special elections; for every $300 the district oversaw, an Area 2 special election would have cost a little over one cent.

Additionally, if election costs were the true issue of concern, then it should be recognized that district elections are even less expensive to hold than at-large elections. If a vacancy occurs, the election only needs to be held within the area versus the entire district. The information presented to the Board acknowledged as much when it was estimated that a special Area 2 election would cost $135,000 and such a districtwide special election was estimated at over $400,000. [91]

If citizen oversight of our democratic institutions is important, then we should hold elections and pay for them when needed. Given the significant resources being overseen by these public agencies, supporting the people in choosing their representatives is critically important for a democratic society.

What is the real price of democracy when it comes to the costs of elections? While decision makers argue that special elections are somehow wasteful and monies could be better spent in other ways, the short-term pennies saved by forgoing elections only purchase longer-term erosion of public trust.

If we believe in democratic representation, we should default to elections.

If we value citizen government oversight of public funds, we should default to elections.

If we honor the American tradition of the peaceful transfers of power, we should default to elections.

Yet another lesson should be taken from this chapter, one that relates to the meaning of representation. With respect to the Area 2 CVUSD Board vacancy, we’ve discussed how elections are the direct democratic way for Area 2 voters to determine who represents them as opposed to filling the vacancy by appointment.

The mere act of appointment aside, one key aspect remains undiscussed regarding the appointment: no one from Area 2 participated in the decision on who represented Area 2.

Residents from other areas – specifically, one person each from Areas 1, 3, 4, and 5 – determined who would sit next to them on the Board representing Area 2. What does representation mean when others except those represented select the representative?

We don’t have members of the House of Representatives selected by other jurisdictions. Imagine the representatives from Georgia or New York or even Northern California determining the representative from Thousand Oaks in the U.S. House. As we noted earlier in this series, this wouldn’t happen; elections for the House of Representatives are guaranteed by the United States Constitution: “When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies.” [92]

When boards or legislative bodies are elected by district, an appointment by the rest of the body to fill a vacancy means that - by construction - those to be represented are completely absent in selecting their own representative. It is the antithesis of representative government, and this fact makes special elections, and the requirement to hold them, even more important for democratic self-governance.

When we rationalize away the need to hold elections, we undermine the very democratic principles that we claim to cherish.

Maintaining a democracy requires a long-term view, so if we believe these values to be important for our society, we need to find ways to remove the impulses and passions that can undermine them in the short-term. The best way to bolster the foundations of our democracy is to remove sources of undemocratic drift.

The critical principle: if we believe in democratic self-governance and in electing our representatives, then we need to hold elections and pay for them when needed. We engage in the electoral process and convince the people to support our view.

[1] Declaration of Independence, United States, July 4, 1776.

[2] Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, The Concept of Representation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 144.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Pitkin, The Concept of Representation, 145. It should be noted that Pitkin’s study was published (1967) at a time when gender inequalities were more pronounced in American society and in its public institutions. As an example from the time of publication, the 90th Congress had only 11 women in the 435-member House of Representatives and 1 female member of the United States Senate, so the use of male gender terms as a generic phrase was used commonly at this time.

[5] Pitkin, The Concept of Representation, 154.

[6] California Constitution (1849), Article IX, Section 1.

[7] “School Board Leadership,” California School Boards Association, West Sacramento, CA, 2007, 3.

[8] “Official Election Summary Report, Gubernatorial General Election, November 3, 1998,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://recorder.countyofventura.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/1998-Nov.-Summary.pdf.

[9] “Official Election Summary, Gubernatorial General Election, November 5, 2002,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://recorder.countyofventura.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/2002-Nov.-Summary.pdf.

[10] “San Luis Obispo County, Presidential Primary Election, March 2, 2004, Official Election Results,” Office of the San Luis Obispo County Clerk-Recorder, https://www.slocounty.ca.gov/Departments/Clerk-Recorder/Forms-Documents/Elections-and-Voting/Past-Elections/Primary-Elections/2004-03-02-Primary/Election-Results-Final-Official-2004-03-02.pdf.

[11] Jean Cowden Moore, “Conejo Valley district trustee to resign,” Ventura County Star, June 18, 2004.

[12] “Official Results, Presidential General Election, November 2, 2004,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://recorder.countyofventura.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/2004-Nov.-Summary.pdf.

[13] “UNFAIR PLAY | Conejo School Board president criticizes LGBTQ inclusion,” Ventura County Reporter, January 11, 2017.

[14] Becca Whitnall, “Andersen wants school districts to have more local control,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, September 25, 2014.

[15] “John Andersen | Conejo Valley Unified School District,” https://web.archive.org/web/20141126193540/http://johnandersen.nationbuilder.com/supporters, retrieved December 26, 2022.

[16] “Official Final, Gubernatorial General Election, November 4, 2014,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Ventura/53334/149606/en/summary.html.

[17] “Official Final, City of Thousand Oaks, Special Municipal Vacancy Election, June 2, 2015,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Ventura/55326/153135/en/summary.html.

[18] Robert Draper, “The Problem of Marjorie Taylor Greene,” The New York Times Magazine, October 17, 2022.

[19] Michelle Conlin and Rich McKay, “The Americans defying Palm Sunday quarantines: 'Satan's trying to keep us apart',” Reuters, April 4, 2020.

[20] Alene Tchekmedyian and Carolyn Cole, “Thousand Oaks councilman, a pastor, resigns, says he’ll defy coronavirus order,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 2020.

[21] https://twitter.com/ASimp805/status/794375466563948544, November 3, 2016.

[22] Andy Nguyen, “Simpson pads fundraising lead with $5K donation,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, October 13, 2016.

[23] Seth McLaughlin, “David Lane’s American Renewal Project mobilizing pastors to run for office,” The Washington Times, June 15, 2015.

[24] “Official Final, General Election, November 8, 2016,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Ventura/63616/184326/en/summary.html.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “School board OKs controversial novel,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, August 17, 2017.

[27] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Board has books on brain heading into summer,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, June 29, 2017.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Megli-Thuna, “School board OKs controversial novel”

[31] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Teachers, trustee clash over literature policy,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 6, 2017.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Trustee takes on book policy,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 9, 2017.

[34] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Mature content ahead,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 16, 2017.

[35] Letter to Mike Dunn, President, Conejo Valley Unified District, from Millie Davis, Director, Intellectual Freedom Center, National Council of Teachers of English, and Chris Finan, Executive Director, National Coalition Against Censorship, November 7, 2017. https://ncac.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Letter-to-CONEJO-NCTE-Nov-2017.pdf

[36] Megli-Thuna, “Trustee takes on book policy”

[37] Acorn Editorial Board, “If anything needs warning label, it’s this school board,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 9, 2017.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Megli-Thuna, “Mature content ahead”

[40] Debate on Item 11A, “Approval of Amendments to Board Policy 6161.1 - Selection and Evaluation of Instructional Materials,” Conejo Valley Unified School District Board Meeting, Video Archive, November 7, 2017.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Alexa D’Angelo, “Conejo Valley school board opts to keep language in literature policy,” Ventura County Star, May 16, 2018.

[44] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Asterisks remain,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, May 16, 2018.

[45] Debate on Item 4C, “Board Review of Board Policy and Administrative Regulation 6161.1 - Selection and Evaluation of Instructional Materials,” Conejo Valley Unified School District Board Meeting, Video Archive, May 15, 2018.

[46] Letter to Mr. John Andersen, Board of Education President, Conejo Valley Unified School District, from Thomas M. Frye, Deputy District Attorney, Office of the Ventura County District Attorney, “Re: Brown Act Complaints – Warning Letter,” May 25, 2018. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4487064-Brown-Act-Letter.html

[47] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “School board majority stands by policy,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, August 30, 2018.

[48] Dawn Megli-Thuna and Kyle Jorrey, “Faced with sharp criticism, CVUSD trustee threatens blogger’s employer,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, January 25, 2018.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Trustee, head of district’s former PR firm lock horns over free speech,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, February 1, 2018.

[51] Wendy Goldstein, “School board should censure colleague,” Letter to the Editor, Thousand Oaks Acorn, February 1, 2018.

[52] Resolution #17/18-10, Governing Board of the Conejo Valley Unified School District, adopted February 8, 2018.

[53] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Dunn opts out of volatile meeting,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, February 6, 2018.

[54] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Chen becomes center of attention in school board race,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, October 18, 2018.

[55] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Everett calls for censure of fellow board member over social media posts,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, October 1, 2018.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] “November 6, 2018, Statewide General Election,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Ventura/89299/Web02.211732/#/.

[63] Debate on Item 3F, “Instructional Services - Approval of Amendments to Board Policy and Administrative Regulation 6161.1 - Selection and Evaluation of Instructional Materials,” Conejo Valley Unified School District Board Meeting, Video Archive, May 7, 2019.

[64] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “School board ends practice of flagging mature books,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, May 16, 2019.

[65] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “School board elections to be decided by districts,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 29, 2018.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

[69] https://supreme.courts.ca.gov/sites/default/files/supremecourt/default/2022-12/pendingissues-civil%20-%20120922.pdf. As of the time of January 2023, the case is still pending.

[70] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Board sets boundaries for future elections,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, February 31, 2019.

[71] Dawn Megli, “Departing trustee didn’t mind a tussle,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, November 26, 2020.

[72] “Official Final Results, November 3, 2020, Presidential General Election,” Office of the Ventura County Clerk and Recorder, https://results.enr.clarityelections.com/CA/Ventura/106266/web.264614/#/summary.

[73] Dawn Megli-Thuna, “Conejo Valley school board president stepping down,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, May 20, 2021.

[74] https://www.facebook.com/jennyfitzgeraldforschoolboard/posts/pfbid02L9rQudfS9JyW7UBBt57YP6WhQ9SZvzRzmQsKSGuCDWCgehRQy1aHAWGyDUXMqSGel, May 20, 2021, retrieved January 3, 2023.

[75] Ibid.

[76] California Education Code Section 5091.

[77] California Education Code Section 5091(a)(1).

[78] California Education Code Section 5091(b).

[79] Resolution #21/22-01, Governing Board of the Conejo Valley Unified School District, adopted July 14, 2021.

[80] Debate on Item B, “Consideration and Action to Approve the Method By Which the Board Member Vacancy Will Be Filled,” Conejo Valley Unified School District Board Meeting, Video Archive, July 14, 2021.

[81] Resolution #21/22-01, CVUSD Board, adopted July 14, 2021.

[82] Minutes of the Conejo Valley Unified School District Board of Education Special Meeting, August 12, 2021.

[83] California Education Code Section 5091(c).

[84] Shivani Patel, “Effort to call for special election of Conejo Valley Unified Area 2 seat fails,” Ventura County Star, October 5, 2021.

[85] Dawn Megli, “School board special election petition fails,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, October 7, 2021.

[86] Dawn Megli, “315 signatures submitted to county seeking election,” Thousand Oaks Acorn, September 16, 2021.

[87] Tracey Kaplan, “Laxdal to Quit Thousand Oaks City Council,” Los Angeles Times, June 28, 1989.

[88] Minutes of the Thousand Oaks City Council, July 11, 1989.

[89] These included vacancies caused by resignations of Linda Parks (2002), Ed Masry (2005), Dennis Gillette (2012), Tom Glancy (2012), Jacqui Irwin (2014), and Rob McCoy (2020).

[90] Financial Audit Reports, Conejo Valley Unified School District, https://www.conejousd.org//site/default.aspx?PageID=1574. Totals include district revenues from 2005 through 2021 - the time period bounded by filling CVUSD Board vacancies.

[91] Debate on Item B, “Consideration and Action to Approve the Method By Which the Board Member Vacancy Will Be Filled,” Conejo Valley Unified School District Board Meeting, Video Archive, July 14, 2021.

[92] United States Constitution, Article I, Section 2, Clause 4.