Can Lessons from Data Science Help Journalism?

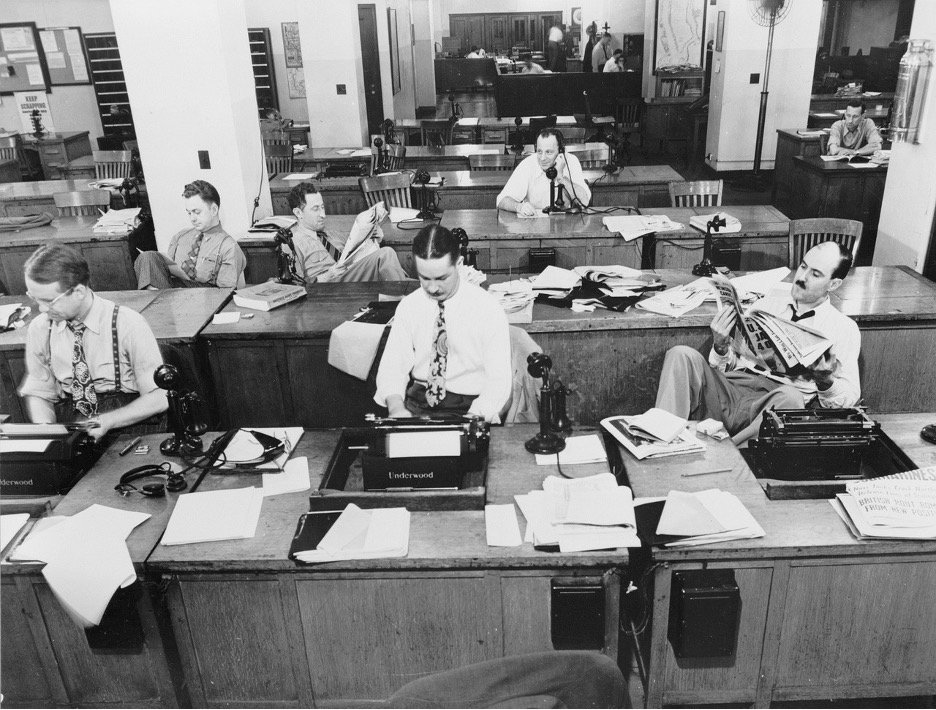

New York Times newsroom 1942. Source: Library of Congress http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c12969

You might think journalism and data science don’t really go together, but on that, I differ. Below are some thoughts on the topic and lessons we can draw from data science on how to make journalism better and more effective in these times.

To begin, my background isn’t journalism, but it is science. I believe that the goals of true journalism are the same as science — get to the truth about what is happening and inform others about that truth.

In decision theory, a topic that I enjoy and in which I have deep practical experience, we learn that there are two primary factors that lead to the decisions we make. One is the most likely explanation for the facts we observe, and the other is our own cost-benefit analysis about what to do as a result.

The first element — finding the most likely explanation for the facts — requires us to be objective about the data we have in front of us. It also requires that we are open to alternative explanations (usually referred to as hypotheses).

The data lead us to the truth, but only when we are asking appropriate questions. Some facts or data may look disparate and unintelligible when viewed collectively, but things can make perfect sense if they are put in the right context. This is where epiphanies can happen — when the most likely explanation for the data finally becomes apparent.

However, some hypotheses might fit the data perfectly yet aren’t at all robust to new information through repeated and independent examination. In data science, we call this a solution that overfits the data. In journalism, this might be called a conspiracy theory — an overly complicated explanation that likely wouldn’t hold up when exposed to new facts.

The truth comes out when the explanation we find is consistent through repeated and independent examination. This holds in science, in journalism, in criminal investigations, or in any other endeavor whose goal is actually to seek the truth.

The second element — evaluating costs and benefits — is different for each decision maker. We can conflate these two elements in our decision making — letting our desire for one outcome cloud our interpretation of the facts in a way to justify the decision.

Much like how a rainbow color scale can fool the eye into seeing sharp gradients in scientific data, journalism has the potential to color the story at the expense of the facts themselves. This can become propaganda (if used intentionally) or can serve the journalistic form itself at the expense of the truth.

Much has also been made about press “objectivity”. From a recent thread (https://twitter.com/KlasfeldReports/status/1011334068275961856) by Adam Klasfled (@KlasfeldReports), referencing work by Walter Lippmann, “neutrality” — a device to convince the reader of one’s accuracy or fairness — is not the same as “objectivity”.

We should strive — whether in journalism or in science — to seek the most likely explanation for the facts and separate out any approaches for assessing the right decision to make as a result. Facts and values should be separate.

In a lesson from decision theory, two decision makers can agree on the facts, and even on the likelihoods of certain explanations, yet *disagree* on the decision to be made. Each decision maker has different tolerances for error or differing ways to assess costs and benefits — in other words, different values.

One example: Sales and Engineering teams within a company can agree on a product and what’s needed to improve it. The Sales team will want to ship the product sooner than the Engineering team, since Sales wants to increase sales (so delay is bad) and Engineering wants to improve the product (so delay is good).

People will still have disagreements because they apply different values to the decision making situation. However, we should *all* strive to make those evaluations on the same set of facts.

That said, that *doesn’t* mean that if there are two possible decisions, there must be given equal treatment. While reporters, investigators, and scientists (and basically all humans) have bias, the lack of equal treatment is not evidence of bias in and of itself.

Some explanations for the facts are not likely, and thus should not really be given much reporting weight. If a plausible explanation for the facts is 10x (or 1000x) more likely than a conspiracy theory, treating each equally unduly injects the values of the conspiracy theorist.

Conspiracy theorists have reasons for choosing the conspiracy over the far more likely plausible explanation — self-rationalization, camaraderie with other true believers, or doubling down as a self-defense of previous choices.

However, journalism should not unwittingly conflate these value judgments in their reporting.

Again, one example is that the government may be actively lying to the public and the press about facts. The free press has an obligation to find the truth and confront the government for how it operates.

Spin around the edges has been practiced by both Democratic and Republican administrations, moving back and forth between liberal and conservative, but within the confines of normality. In science, this might be described as working within the linear regime.

Previous rules of thumb — such as “if the President says it, it’s news” or “we present what he says, the viewers can decide whether it’s true” — can work as effective operating principles in the linear regime.

However, what is happening now has broken past the linear regime. The President and his staff are lying — verifiably, directly and without remorse — on a daily basis. With this, we have entered the nonlinear regime, so our approach to coverage must evolve to remain objective to the truth.

In science, we may have had an experimental setup that was working just fine, maybe with some hiccups and tweaks along the way. However, if suddenly the data start to look very different, we should question what is happening with our setup and look for other explanations.

This doesn’t mean that we give up on our scientific objectivity. It does mean, though, that we can’t interpret the data the way we used to, since conditions on the ground have changed. We have to apply our same principles, but to a new problem. The same goes for journalism.

If we focus on the goals of journalism and the new facts on the ground, we will get to a better objective explanation of the facts and serve journalism and its audience better in these changing times.